A Visit to a Welsh Coal Mine

In November 1954, Henry visited a Welsh coal mine, Llanhilleth, with his friend Terry Williams. Many of Terry’s friends and relations lived in the village of Llanhilleth and were employed at the colliery, indeed Terry’s father worked a haulage engine underground.

Henry sent an account of the visit to his parents, which is copied below.

I have just returned to Cambridge to-day, after a most interesting long week end in South Wales with Terry. On Monday, we went down the Llanhilleth coal mine. It proved more difficult than we had thought, we had to apply for permission to the Area General Manager of the particular group of coal mines – even the manager of the pit himself cannot give permission. On receiving Terry’s letter, which Terry wrote in the N.C.B. office, the Area General Manager ‘phoned through to the manager of the Llanhilleth Pit, who took us down, with his assistant manager – combining it with his official inspecting duties.

First he explained the geology and geography of the seams with the aid of maps, in his office. Then we went down, slowly, in the “cage”, and he pointed out to us the earlier workings and galleries on the way. The seam which is being worked is some 330 yards down. On arriving at that level, we got out and walked along a fairly brightly lit tunnel toward the particular coal face we were to visit – there are several faces being worked down the same mine. Coal is hauled away from the conveyor belts which bring it from the face in heavily built iron wagons, and the tunnels in which these run back towards the pit shaft – which are of course, old workings – are rather larger than or about the same size as a tube tunnel, with two “tracks” on which the wagons run. These are moved by a stationery compressed air or electric engine acting on an endless rope. The maximum length of the “train” is of 22 wagons. And they are taken to the surface two at a time in the “cage”. The same cage is used for coal wagons and men, but the operator always knows when men are on and operates the winding engine a little more slowly.

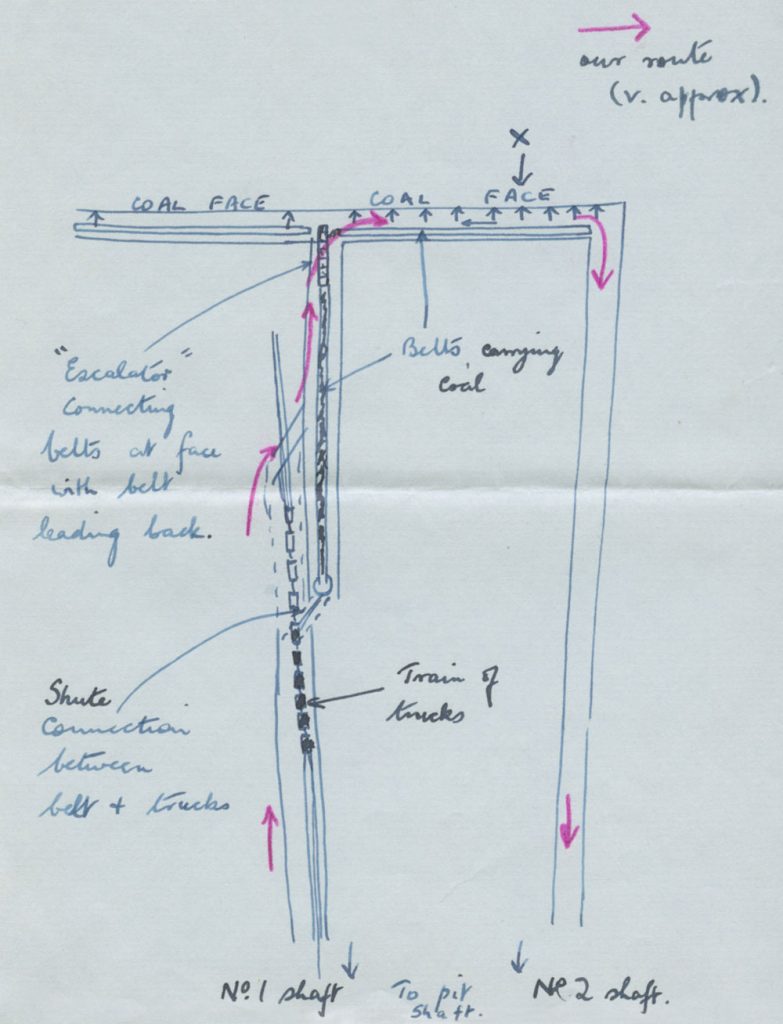

I’m not sure of the exact geography of the tunnels, I’m afraid – there were so many of them heading up and down to various older galleries – but eventually we got to the coal face through a tunnel with a conveyor belt in it which was bringing back coal. This ended in a kind of steel “escalator”, which received coal from belts at right angles to its own direction. It’s rather a job to explain this quite clearly, so I’ve put in a little diagram!

The coal-face itself is being attacked by compressed-air drills and picks by miners (“colliers”) stationed along it, and they shovel the coal directly onto the conveyor belt which runs immediately behind them. They work in a very confined space, not more than four feet high, and advance, as you see from diagram, along a broad front. The roof is shored up here with pit props, in a special sort of way. It is arranged that by knocking down certain key props (steel ones) the roof comes down. This is because as coal is cut away and the face advances a large cave tends to arise. However, if this was left, the pressure of the roof would tend to crush the face, so as advance is made, the conveyor belt is moved forward, and the props knocked away behind so that the roof falls and weight is taken at the back.

At the time we went along the face, they were having trouble due to an irregularity of very hard stone about at X on diagram which was difficult to clear away. All along the face one had to crouch along: at this point it was hands and knees. We did not see any coal-cutting machines in action, one was there but partly buried in coal and not operating due to the hold-up. The coal-cutters are “lubricated” with water, and water is also sprayed out of special nozzles onto the coal where it falls off the belts from the face onto the “escalator”. This is to remove dangerous coal dust from the atmosphere. Apparently only dust of a size of 1 – 5 microns diameter (i.e. 1/200th to 1/1000 of one millimetre) is dangerous to breathe in, and this is periodically tested for by a “dust sampler”.

After wriggling along the length of one half of the face (as shown!), we returned to the other pit shaft in the colliery by another route.

I should mention here two points. Conveyor belts are a surprisingly heavy item of expenditure, and although naturally very heavily made of laminate canvas and rubber are readily damaged if chafed. For right-angled turns the “escalators” are best used. Expense of up to 5/6 per ton of coal can be incurred through belt wear alone, though in the last month’s balance sheet belt wear was only 11d per ton of coal.

The second point is that we found a magnificent patch of fossil leaf-bases of Lepidodendron – a coal-measure plant like a tree fern on the roof of the face , which the manager kindly presented us with. I mut show you these some time!

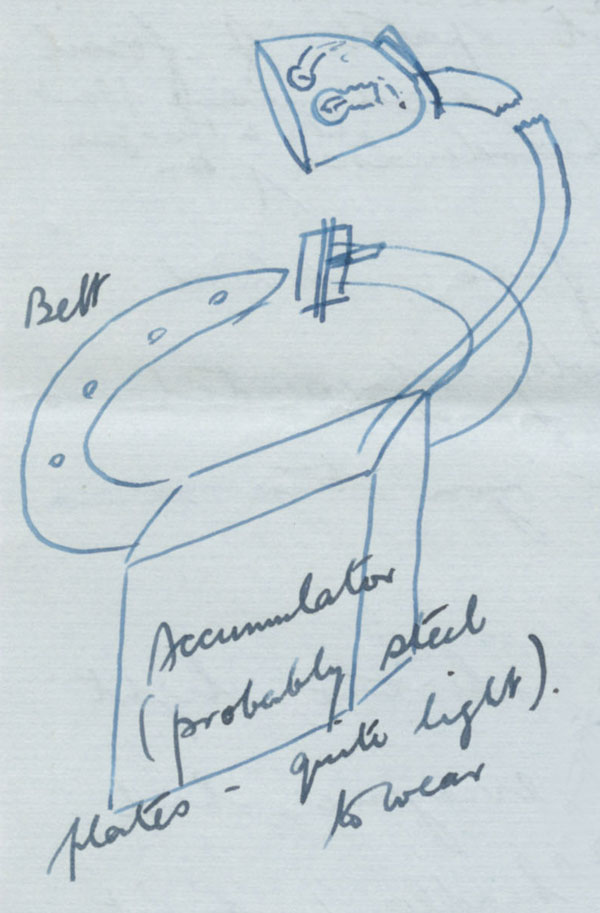

There was some electric light in the pit, but everyone had a helmet with a headlamp on it. Before going down the pit, each miner (or manager, or visitor) passes through a turnstile into a lamp-room, where some five hundred accumulators are charging, each with its headlamp attached by a piece of cab tyre flex. The man then removes his accumulator from the rack, fastents it onto his special belt, and fits the headlamp onto his helmet. Enough current is provided for about 12 hours continuous light per charging. Two bulbs are present in each “headlamp” like in the headlamp of a car, a big centre one and a reserve dim one. In Llanhilleth pit, these lamps have only been available some 6 years. The genuine old oil Davy Lamps, classical pattern, were still in evidence here and there.

As the man removed his lamp, he replaces a brass check on its hook, showing thereby that he is down the mine, so that his whereabouts are known in case of an accident.

We left the pit by another shaft, and shot very rapidly to the surface in the cage. Usually one does ascend and descend with extraordinary speed – a real “super”-lift, but going down we went slowly to see the old galleries. In a sense this was hard luck, because it’s supposed to be a most odd feeling going down at this speed for the first time! Better than the average fun-fair gadgets!

The winding engine is an old steam engine built in 1890. It’s due to be replaced soon by an electric motor, which will cut costs, it’s estimated, by 9/10ths. Costs in fuel and in boiler maintenance and wages. Until comparatively recently, a beam engine pumped water out of the pit.

Naturally, there is a ventilation system, air being fanned down a ventilation shaft. It is induced to follow its correct course through the workings by doors so placed as to restrict air movement down some of these. We went through one – rather uncanny, one has to push very hard to open the door – in fact I could not open it! – and then there’s no rush of air such as might be expected. Just a pressure.

After the tour the manager took us back into his office where we asked questions and had quite a long talk. He was on a productivity mission to America fairly recently, and found the American system was thoroughly mechanised and worked very well. But then they have some very big seams (20-40 feet) in which they run a kind of trolleybus transport on overhead wires. Talking about the danger of explosions from sparks, sparks from electrical machinery are not particularly dangerous in well-ventilated mines since they emit much light but little heat, the dangerous ones are the red hot glowing kind, of relatively long duration.

Nationalisation is universally looked upon as an absolute necessity. In this mine, the best seam was worked out many years ago; it was a thick one of the best quality coal. Now the less productive and more difficult seams have to be used.

Concerning strikes, an official strike is almost unheard of at Llanhilleth, but unofficial strikes are not as rare. The basic reasons for these are apparently two – good earnings by the men resulting in quite a bit of excess cash for a day out, and a few troublesome men who dig up imagined grievences. The manager, a miner himself during the depression times, said he was always uneasy at the start of each shift, since a strike may be threatening at almost any time. He has known of cases where he was dealing with an alleged grievence, and at the same time buses had been ordered for a trip! His job is a most responsible one, calling for knowledge ranging from mining geology to psychology, law and office-work. We thought him, and his assistant manager, really fine men, with a tremendous sense of responsibility.

Afterwards, on Monday afternoon, we went to see the surface mining, the open-cast machinery on the local mountain top. We saw it (the main excavator) from far off, looking like an enormous prehistoric monster, towering into the air. The grab is capable of a 40 ton bite. We got to it, and found it surrounded by a sea of slosh. We weren’t really prepared for this, but nevertheless wanted to have a close look at the monster and the hole it had eaten out of the hilltop, so marched into it. The machine was out of order, a cable had broken – one of the cables connecting the grab to the machine, and was being cut off square by oxy-acetylene torch. The broken part had splayed out like the end of a piece of frayed string – with the difference that when they’d cut the piece off square, and the end was “thrown away” – three or four men had to totter off with it! I reckon the size of the gadget to be equal to four large houses. A great artificial valley stretched away from the slosh on which the monster was standing motionless. It must have been half a mile long, some 80 feet deep and perhaps 100 yards wide, with a coal black floor on which “teeth marks” could plainly be seen. The big machine was connected up to a line of pylons by an enormous cab tyre cable, some 4” across.

It was a desolate rainy day, and we came away with the feeling that open-cast was worse than deep mining. By this time we’d both got “bootfulls” of slosh, Terry had sunk in nearly up to his knees following an incautious stop. I hadn’t got further than the upper ankle level. But it was worth it to see the “monster”.

A third type of mining is carried out on the hillsides, where small tunnels run in to coal seams fairly high up on the hill. We saw one such on the Saturday, it occupied 16 men, was “mechanised” by ponies and trolley-tracks, and yielded 16 tons of coal per day. Run still by private enterprise, not more than 20 men may be employed and all coal sold to the coal board.

Well, I really feel this is almost enough about mining, but I had a most interesting time observing the processes for the first time, and felt I ought to write to you about them.

Henry, letter to parents, November 1954.

At the end, Henry added a postscript:

P.S. Nearly a whole pad of paper! Didn’t expect the epistle to be so long!